Humans used northern migration routes to reach eastern Asia

New article suggests wetter climates may have allowed Homo sapiens to expand across the deserts of Central Asia by 50-30,000 years ago

Northern and Central Asia have been neglected in studies of early human migration, with deserts and mountains being considered uncompromising barriers. However, a new study by an international team argues that humans may have moved through these extreme settings in the past under wetter conditions. We must now reconsider where we look for the earliest traces of our species in northern Asia, as well as the zones of potential interaction with other hominins such as Neanderthals and Denisovans.

Archaeologists and palaeoanthropologists are increasingly interested in discovering the environments facing the earliest members of our species, Homo sapiens, as it moved into new parts of Eurasia in the Late Pleistocene (125,000-12,000 years ago). Much attention has focused on a ‘southern’ route around the Indian Ocean, with Northern and Central Asia being somewhat neglected. However, in a paper published in PLOS ONE, scientists of the Max Planck Institute for the History of Human Science in Jena, Germany, and colleagues at the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology in Beijing, China, argue that climate change may have made this a particularly dynamic region of hominin dispersal, interaction, and adaptation, and a crucial corridor for movement.

‘Heading North’ Out of Africa and into Asia

“Archaeological discussions of the migration routes of Pleistocene Homo sapiens have often focused on a ‘coastal’ route from Africa to Australia, skirting around India and Southeast Asia,” says Professor Michael Petraglia of the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, a co-author of the new study. “In the context of northern Asia, a route into Siberia has been preferred, avoiding deserts such as the Gobi.” Yet over the past ten years, a variety of evidence has emerged that has suggested that areas considered inhospitable today might not have always been so in the past.

“Our previous work in Saudi Arabia, and work in the Thar Desert of India, has been key in highlighting that survey work in previously neglected regions can yield new insights into human routes and adaptations,” says Petraglia. Indeed, if Homo sapiens could cross what is now the Arabian Deserts then what would have stopped it crossing other currently arid regions such as the Gobi Desert, the Junggar Basin, and the Taklamakan Desert at different points in the past? Similarly, the Altai Mountains, the Tien Shan and the Tibetan Plateau represent a potentially new high altitude window into human evolution, especially given the recent Denisovan findings from Denisova Cave in Russia and at the Baishiya Karst Cave in China.

Nevertheless, traditional research areas, a density of archaeological sites, and assumptions about the persistence of environmental ‘extremes’ in the past has led to a focus on Siberia, rather than the potential for interior routes of human movement across northern Asia.

A “Green Gobi”?

Indeed, palaeoclimatic research in Central Asia has increasingly accumulated evidence of past lake extents, past records of changing precipitation amounts, and changing glacial extents in mountain regions, which suggest that environments could have varied dramatically in this part of the world over the course of the Pleistocene. However, the dating of many of these environmental transitions has remained broad in scale, and these records have not yet been incorporated into archaeological discussions of human arrival in northern and Central Asia.

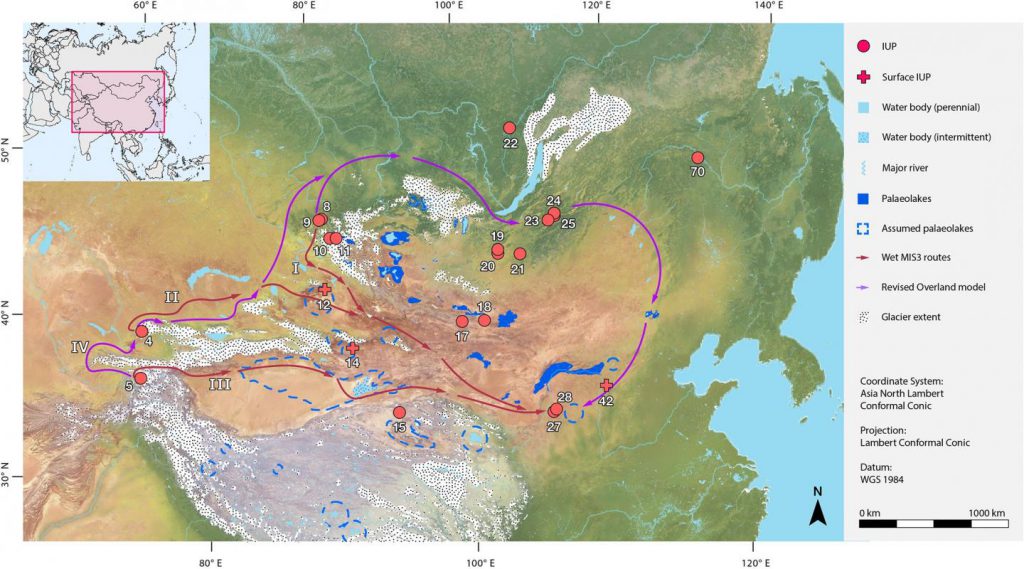

“We factored in climate records and geographical features into GIS models for glacials (periods during which the polar ice caps were at their greatest extent) and interstadials (periods during the retreat of these ice caps) to test whether the direction of past human movement would vary, based on the presence of these environmental barriers,” says Nils Vanwezer, PhD student at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History and a joint lead-author of the study.

“We found that while during ‘glacial’ conditions humans would indeed likely have been forced to travel via a northern arc through southern Siberia, during wetter conditions a number of alternative pathways would have been possible, including across a ‘green’ Gobi Desert,” he continues. Comparisons with the available palaeoenvironmental records confirm that local and regional conditions would have been very different in these parts of Asia in the past, making these ‘route’ models a definite possibility for human movement.

Where did you come from, where did you go?

“We should emphasize that these routes are not ‘real’, definite pathways of Pleistocene human movement. However, they do suggest that we should look for human presence, migration, and interaction with other hominins in new parts of Asia that have been neglected as static voids of archaeology,” says Dr. Patrick Roberts also of the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, co-author of the study. “Given what we are increasingly discovering about the flexibility of our species, it would be of no surprise if we were to find early Homo sapiens in the middle of modern deserts or mountainous glacial sheets.”

“These models will stimulate new survey and fieldwork in previously forgotten regions of northern and Central Asia,” says Professor Nicole Boivin, Director of the Department of Archaeology at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, and co-author of the study. “Our next task is to undertake this work, which we will be doing in the next few years with an aim to test these new potential models of human arrival in these parts of Asia.”

Press release from the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History / Max-Planck-Instituts für Menschheitsgeschichte

Homo sapiens may have had several routes of dispersal across Asia in the Late Pleistocene

A new model identifies unexpected potential paths for the spread of human culture and technology

Homo sapiens may have had a variety of routes to choose from while dispersing across Asia during the Late Pleistocene Epoch, according to a study released May 29, 2019 in the open-access journal PLOS ONE by Feng Li of the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology in Beijing and colleagues.

After leaving Africa, Homo sapiens dispersed across the Asian continent during the Late Pleistocene, but it isn’t known exactly what routes our species followed. Most models assume that the Gobi Desert and Altai Mountain chains of North and Central Asia formed impassable barriers on the way to the east, so archaeological exploration has tended to neglect those regions in favor of seemingly more likely paths farther north and south.

In this study, Li and colleagues use Geographic Information Systems (GIS) software alongside archaeological and paleoclimate data to reconstruct the conditions of North and Central Asia over the Late Pleistocene and to identify possible routes of travel. Their data suggest that the desert and mountain regions were likely impassable during cold and dry glacial periods, but that during warmer and wetter interglacial times it would have been possible for human populations to traverse these regions via at least three routes following ancient lake and river systems.

The authors caution that these data do not demonstrate definite routes of dispersal and that more detailed models should be constructed to test these results. However, these models do identify specific routes that may be good candidates for future archaeological exploration. Understanding the timing and tempo of Homo sapiens dispersal across Asia will be crucial for determining how culture and technology spread and developed, as well as how our species interacted with our extinct cousins, the Neanderthals and Denisovans.

Roberts adds: “Our modelling of the available geographic and past climate data suggest that archaeologists and anthropologists should look for early human presence, migration, and interaction with other hominins in new parts of Asia that have been neglected as static voids. Given what we are increasingly discovering about the flexibility of our species, it would be of no surprise if we were to find early Homo sapiens in the middle of modern deserts or mountainous glacial sheets all across Asia. Indeed, it may be here that the key to our species’ uniqueness lies”.

###

Citation: Li F, Vanwezer N, Boivin N, Gao X, Ott F, Petraglia M, et al. (2019) Heading north: Late Pleistocene environments and human dispersals in central and eastern Asia. PLoS ONE 14(5): e0216433. https:/

Funding: This study was funded by Max-Planck-Gesellschaft (DE) to Nicole Boivin, Strategic Priority Research Program of Chinese Academy of Sciences grant XDB26000000 to Feng Li, and Youth Innovation Promotion Association of the Chinese Academy of Sciences grant 2017102 to Feng Li. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Press release from the Public Library of Sciences