Study provides evidence that the domestication of pigs from wild boars occurred in South China

Microfossils on 8,000-year-old pig teeth show pigs ate human foods and waste.

Pigs have long been known, sometimes celebrated, as among the most intelligent of farm animals. Now, a new Dartmouth-led study provides evidence that pigs were first domesticated from wild boars in South China approximately 8,000 years ago.

China has long been considered one of the locations for original pig domestication but tracking the initial process has always been challenging. The study is the first to find that pigs were eating humans’ cooked foods and waste. The results are reported in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Domestication of some animals, including pigs, has often been associated with the Neolithic period when humans began their transition from foraging to farming around 10,000 years ago.

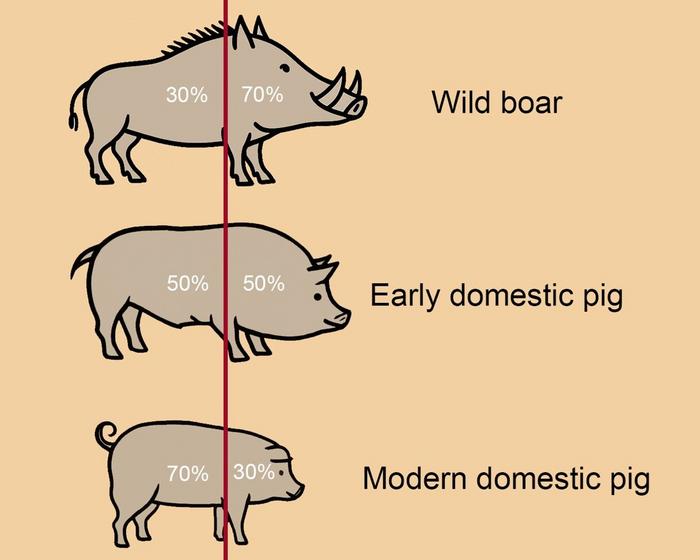

Wild boars are large, aggressive beasts that live independently, many in the forest, rooting for food from the undergrowth. They have larger heads and mouths, and bigger teeth than domestic pigs.

“While most wild boars are naturally aggressive, some are more friendly and less afraid of people, which are the ones that may live alongside humans,” says lead author Jiajing Wang, an assistant professor of anthropology at Dartmouth. “Living with humans gave them easy access to food, so they no longer needed to maintain their robust physiques.”

“Over time, their bodies became smaller, and their brains also became smaller by about one-third,” says Wang.

To study the domestication of pigs and other animals, archaeologists have often relied on examining the sizes and shapes of skeletal structures to mark the morphological change over time.

“But this method can be problematic because the reduction in body size likely occurred later in the domestication process,” says Wang. “What probably came first were behavioral changes, like becoming less aggressive and more tolerant of humans,” says Wang.

So, for the study, the researchers used a different method and documented what the pigs had been eating over their lifespan using the molar teeth of 32 pig specimens. Through a microfossil analysis of the pig teeth, they examined the mineralized plaque, known as dental calculus, from two of the earliest sites where humans lived, at least 8,000 years ago at Jingtoushan and Kuahuqiao in the Lower Yangtze River region of South China.

The sites were waterlogged, which helped preserve the organic materials.

The analysis found a total of 240 starch granules present. It revealed that pigs had eaten cooked foods—rice and yams—as well as an unidentified tuber, acorns, and wild grasses.

“These are plants that were present in the environment at that time and were found in human settlements,” says Wang.

Prior research has found rice at both sites with intensive rice cultivation at Kuahuqiao, which is located farther inland and has greater access to freshwater than coastal-based Jingtoushan. Other studies have also shown starch residues in grinding stones and pottery from Kuahuqiao.

“We can assume that pigs do not cook food for themselves, so they were probably getting the food from humans either by being fed by them and/or scavenging human food,” says Wang.

Human parasite eggs, specifically, that of whipworm, aka Trichuris —a parasite egg that can mature inside human digestive systems—were also found in the pig dental calculus. These yellow-brown football-shaped parasite eggs were found in 16 of the pig teeth specimens. The pigs must have been eating human feces or drinking water or eating food for which the dirt was contaminated by such feces, according to the study.

“Pigs are known for their habit of eating human waste, so that is additional evidence that these pigs were probably living with humans or having a very close relationship with them,” says Wang.

The researchers also conducted a statistical analysis of the dental structures of the Kuahuqiao and Jingtoushan pig specimens, showing that some had small teeth similar to those of modern domestic populations in China.

“Wild boars were probably attracted to human settlements as people started settling down and began growing their own food,” says Wang. “These settlements created a large amount of waste, and that waste attracts scavengers for food, which in turn fosters selection mechanisms that favored animals willing to live alongside humans.”

In animal domestication, this process is called a “commensal pathway,” where the animal is attracted to human settlements rather than the humans trying to actively recruit the animals.

The data also supports that early interaction also involved domestic pigs under active human management, representing a “prey pathway” in the domestication process.

“Our study shows that some wild boars took the first step towards domestication by scavenging human waste,” says Wang.

The research also sheds light on the likely relationship between pig domestication and the transmission of parasitic diseases in early sedentary communities.

Yiyi Tang, Guarini, a graduate student in Wang’s lab; Yunfei Zheng, Leping Jiang, and Guoping Sun at the Zhejiang Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology; Xiaolin Ma at Henan Museum; and Yanfeng Hou at Henan Provincial Institute of Cultural Heritage and Archaeology also contributed to the study.

Bibliographic information:

J. Wang,Y. Tang,Y. Zheng,L. Jiang,X. Ma,Y. Hou,& G. Sun, Early evidence for pig domestication (8,000 cal. BP) in the Lower Yangtze, South China, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. (2025) 122 (24) e2507123122, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2507123122

Press release from Dartmouth College.