The Norwegian Code of the Realm laid the foundation for how Norwegians understand – and trust – the law today

Medieval Norwegians felt King Magnus VI’s Code of the Realm was fair when it was introduced as one of the first laws of its kind in Europe. For more than 500 years, this law has helped give Norwegian people a relatively high level of trust in their judicial system.

In 1274, King Magnus VI, the Law Mender, united the entire Norwegian kingdom under one common law. The Norwegian Code of the Realm remained in force for over 400 years, and in it lie the seeds that would grow into Norway’s rule of law and the idea of popular co-determination.

The Norwegian Code of the Realm is one of the most important historical documents we have in Norway.

Some 750 years ago, Norway established a law that applied to the whole country, making it one of the first kingdoms in Europe with such a law. Only Sicily and Castile in Spain introduced similar laws earlier, but they were not as successful as the Norwegian Code of the Realm.

Norway became a pioneering country in this area, not least because the law worked so well and was in use for so long. Towns were classed as separate legislative areas and received a separate Code of the Towns in 1276.

The Birkebeiners ascended to the throne after a hundred years of civil war

The background to King Magnus VI uniting Norway under one common law was 100 years of power struggles and civil war. The Birkebeiners and the Baglers fought each other in the final phase of the dispute over the right to and control of the throne.

The Birkebeiners had to flee with the young son of King Haakon Haakonsson from Eastern Norway to Nidaros in order to bring him to safety, and the dramatic escape took place on skis.

Haakon Haakonsson eventually gained power in Norway as the sole king and began a phase in Norwegian medieval history that saw the kingdom’s power and position considerably strengthened.

His son Magnus VI continued to develop and strengthen the monarchy, and he became known as Magnus the Law Mender because of the Code of the Realm he introduced, in which he ‘mended’ the laws. ‘Law mender’ refers to the fact that he implemented the most comprehensive legislative reform ever carried out in Norway.

Not only was this a comprehensive undertaking; the content of the Code also inspired confidence and trust in the law – a legacy that still permeates Norwegian society today.

“Norwegian society is a society governed by law, with a long legal tradition. We generally have a high level of trust in the law and public administration, and an important reason for this lies in Norway’s history and Magnus VI’s Code of the Realm,”

says Erik Opsahl, Professor of Medieval History and head of the Centre for Medieval Studies at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU).

Important for Norwegian identity

Magnus VI’s Norwegian Code of the Realm has also been important in creating and maintaining a common Norwegian identity and awareness of a Norwegian society during the long union with Denmark, which lasted for 400 years. The Norwegian Code of the Realm helped to maintain Norway as a separate legislative area within the union.

“For many hundreds of years, we were part of a larger political system, and the Norwegian Code of the Realm was an important foundation for Norwegian values during the union years.

The Norwegian Code of the Realm is an important institution in Norwegian history, and although Norway was strongly influenced by Danish law and administration in the union, Norwegian law was nevertheless the starting point for the rule of the union monarchs in Norway,” says Opsahl.

A humane law that safeguarded the vulnerable

The new law abolished revenge killings, and it was no longer permitted to carry out vendettas. Previously, it had been expected that family and relatives would avenge murder with murder. The new law also restricted the practice of taking the law into one’s own hands.

“This breaks with old traditions and marks a step towards a modern mindset where individual responsibility is more evident. The Code also shows great awareness of society’s duty to take extra care of vulnerable individuals,” says Erik Opsahl.

For example, the poor were not to be punished if they stole food to feed themselves or their family members. They were classed as ‘the worthy needy’.

“The law was perceived as fair, and it provided predictability and security. It was clearly not perceived as an instrument used by the elite to protect their own rights and interests. If the Norwegian Code of the Realm had been perceived as bad and unfair, it would not have become as firmly rooted as it did,” says Erik Opsahl.

Laymen took on the role of lay judges

Previously, the country had been divided into four legislative areas, each with its own assembly that functioned as a court: Frostating, Gulating, Eidsivating and Borgarting.

The four assemblies remained important meeting places and courts, but they fell under a common law in 1274 and became more closely aligned with the nationwide royal administrative apparatus.

Next to the judge, the ‘lawspeaker’, there were laymen who took on the role of lay judges in the assembly.

“Although there are obvious risks in drawing long historical lines, it can be claimed that traces of Magnus VI’s Code of the Realm can still be found in today’s Norwegian legal system, with a large proportion of lay people in the courts, and with a simpler and more directly hierarchical court system than in many other countries,” says Opsahl.

Use of discretion

One of the reasons the Norwegian Code of the Realm gained such a firm foothold was that it was established locally. The Code states that

only a fool keeps to the letter of the law if the law is too strict or too lenient.

Instead, the Code was to be used to pass fair judgement, and the text was intended as a starting point that could then be adapted locally.

The way it worked was that lawspeakers appointed by the King travelled around and collaborated with local lay judges to pass judgements.

In other words, the Norwegian Code of the Realm facilitated the use of discretion.

“And when the law facilitates the use of discretion, it also facilitates dialogue,” says Erik Opsahl.

The Norwegian Code of the Realm laid the foundation for trust in the judicial system.

“Then there is a discussion about whether this trust can sometimes result in people being a little naive towards the government and politicians. Corruption in one form or another seems to be more prevalent in Norway than we like to think. It also seems that Norwegians sometimes have problems fully understanding impartiality,” says Opsahl.

A model for other countries

The Norwegian Code of the Realm most likely served as a model for the Swedish Code of the Realm that was introduced around 1350. The various parts of the Norwegian monarchs’ kingdom in the High Middle Ages, popularly called the ‘Norwegian Realm’, were either directly governed by the Norwegian Code of the Realm, such as Shetland and the Faroe Islands, or received their own variant, such as Iceland.

Iceland turned to Norway and King Magnus VI for help in drafting an Icelandic law that could restore law and order after a period of unrest in the country.

The power of the church and the King

Magnus IV’s Norwegian Code of the Realm became a unifying Norwegian symbol over time.

During the Middle Ages, what we today call state power was divided between the monarchy and the church. In the 13th century, the church and the king operated side by side, where both had the power and authority to be both legislative and judicial.

The Law of the Realm did not clarify where the boundary between these two powers should be. King Magnus then entered into an agreement with the church, the Sættargjerden (settlement), in 1273 and 1277.

The agreement appeared to be a compromise, but Magnus’ successors refused to approve the agreement because it was perceived as giving the church too much power. Only in 1458 was it approved by Kristian I, the union king.

The Danish era

Magnus IV’s Norwegian Code of the Realm had an important place in Norwegian society from the time it was introduced until 1687. Even when Norway became subject to Denmark as a sovereign during the Reformation in 1537, the Norwegian law continued to apply.

When the Danish “coup maker” Christian III sent his son Fredrik (later Fredrik II) to Norway as a representative of his father and himself to be honoured, the Danish king Christian instructed his son that he should promise on behalf of his father and himself to rule the Norwegians by “the laws of Saint Olav and the Kingdom of Norway”.

A unique and well-used copy

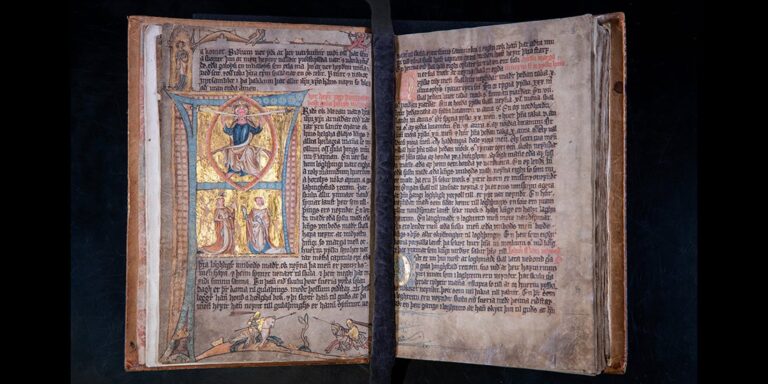

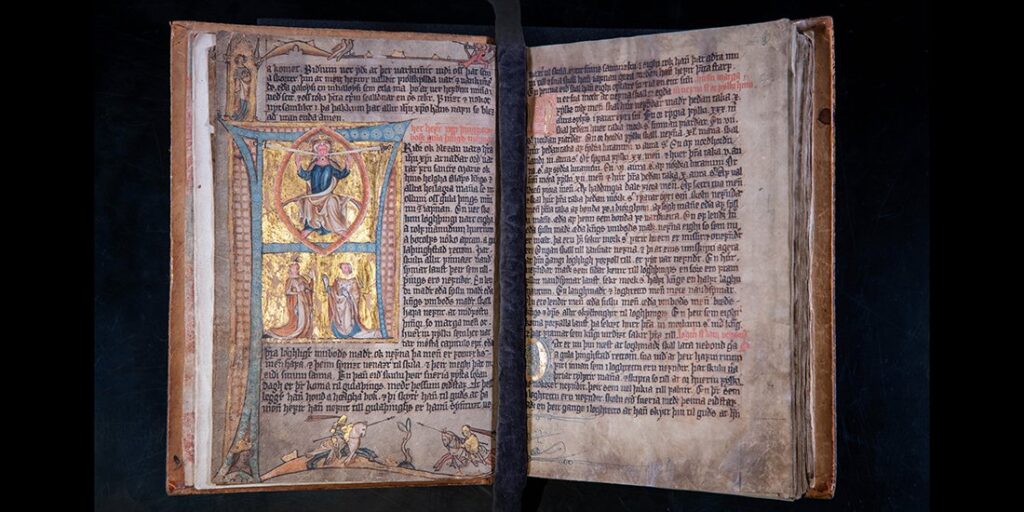

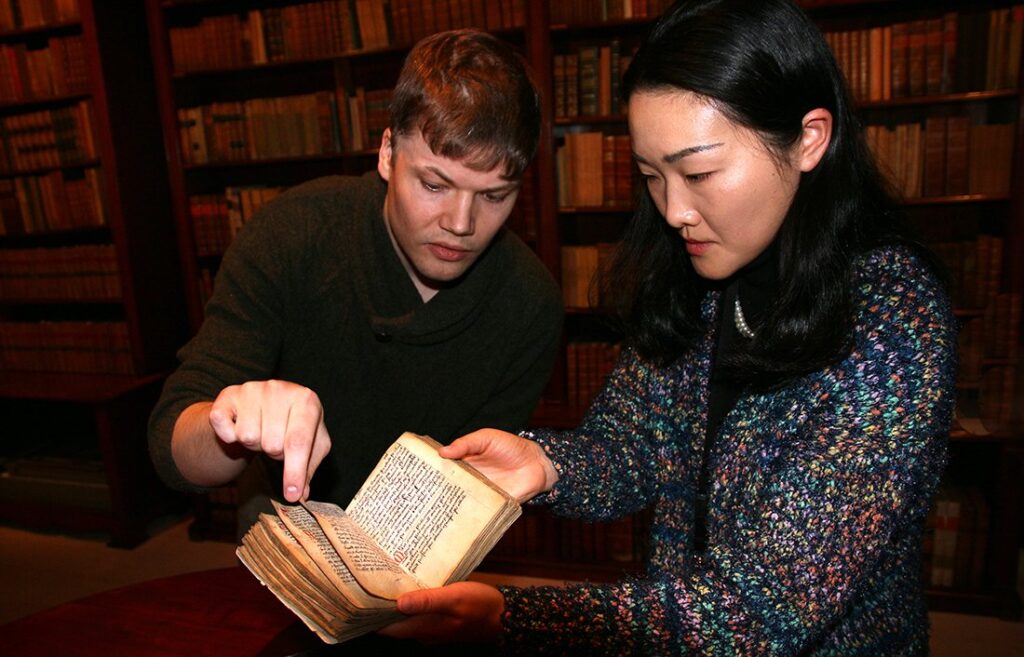

There are 42 surviving copies of Magnus VI’s Norwegian Code of the Realm. Three of them are in Norwegian ownership, and one of these is located in the Gunnerus Library in Trondheim.

This is a copy that was meant for everyday use, more like a pocket law book that lawspeakers could easily carry around on their travels when visiting the local courts. The copy is from the latter half of the 14th century and bears signs of frequent use.

“This copy of Magnus VI’s Norwegian Code of the Realm is one of the most important items we have in our collection. It is one of the few surviving books we have in Norway written in Old Norse. As the Danish era progressed, the Norse language disappeared, so this law book represents an important element in Norwegian history and identity,”

says Per-Olav Broback Rasch, historian and Research Librarian at NTNU University Library’s Special Collections.

When Norway left the union with Denmark, anything that referred to Norwegian identity, culture and history became very important. This unique copy of Magnus VI’s Norwegian Code of the Realm is part of that heritage.

Per-Olav Broback Rasch says that it has been owned by Christoffer Hammer. Hammer was a government official, author, and collector. In 1804, his extensive library (2000 volumes), a collection of natural rarities and 20,000 coins were bequeathed to the Royal Norwegian Society of Sciences and Letters (DKNVS) in Trondheim.

Hammer’s legacy enabled DKNVS to function as a research council, which was of great importance in the 1800s as research funding was difficult to obtain.

Press release from The Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU), by Idun Haugan