Intricate settlements found in the Llanos de Mojos, Amazonia

Newly discovered ancient Amazonian cities reveal how urban landscapes were built without harming nature

A newly discovered network of “lost” ancient cities in the Amazon could provide a pivotal new insight into how ancient civilisations combined the construction of vast urban landscapes while living alongside nature.

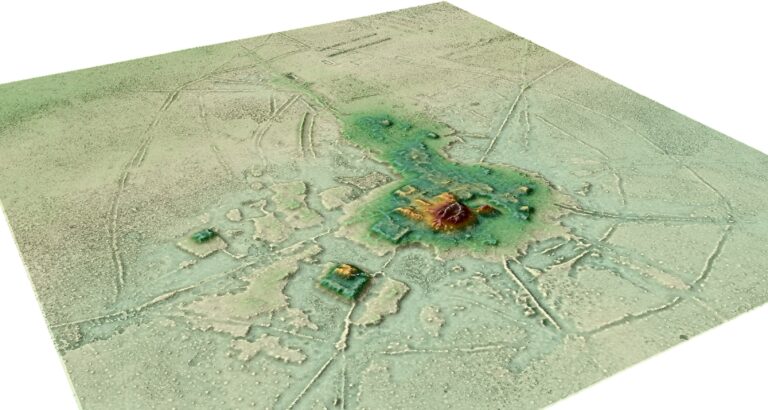

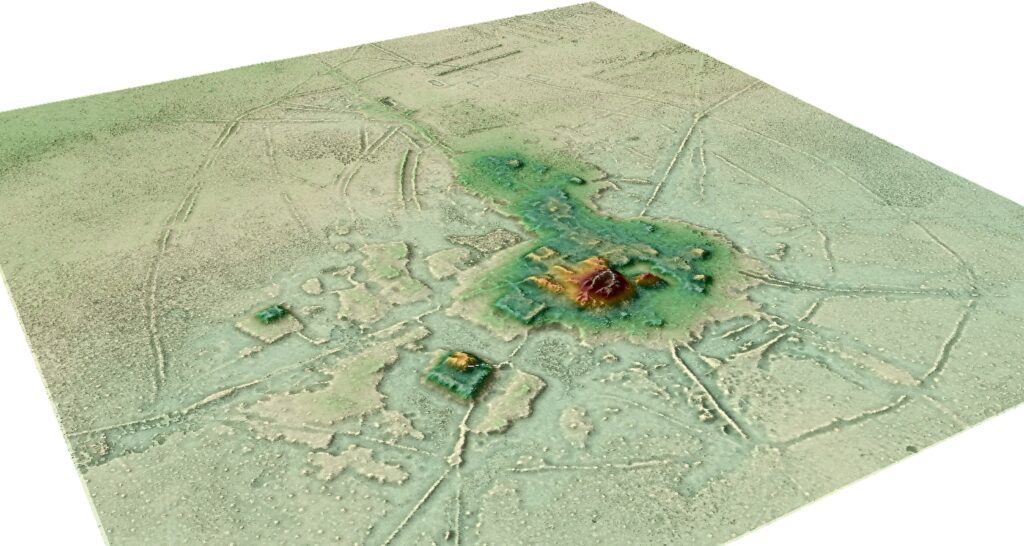

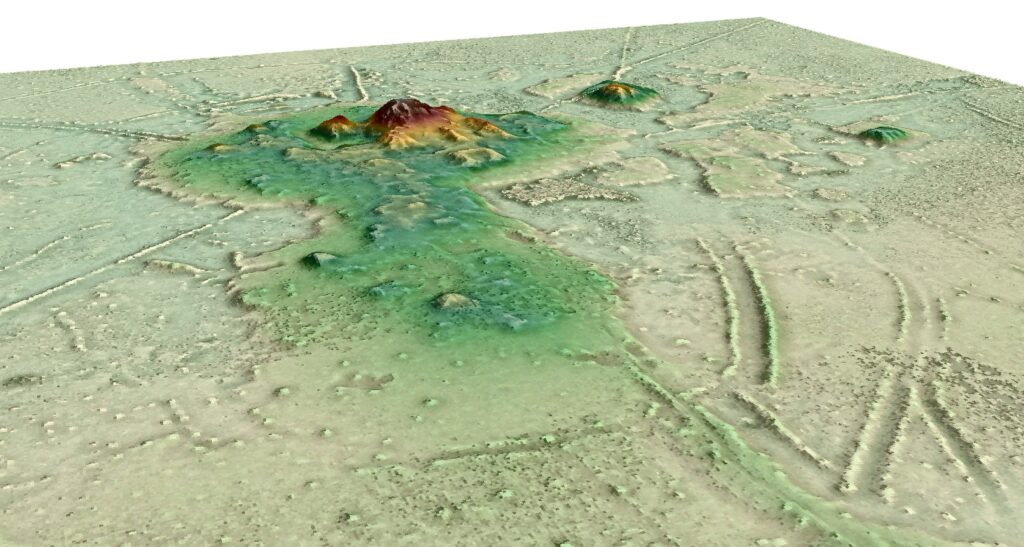

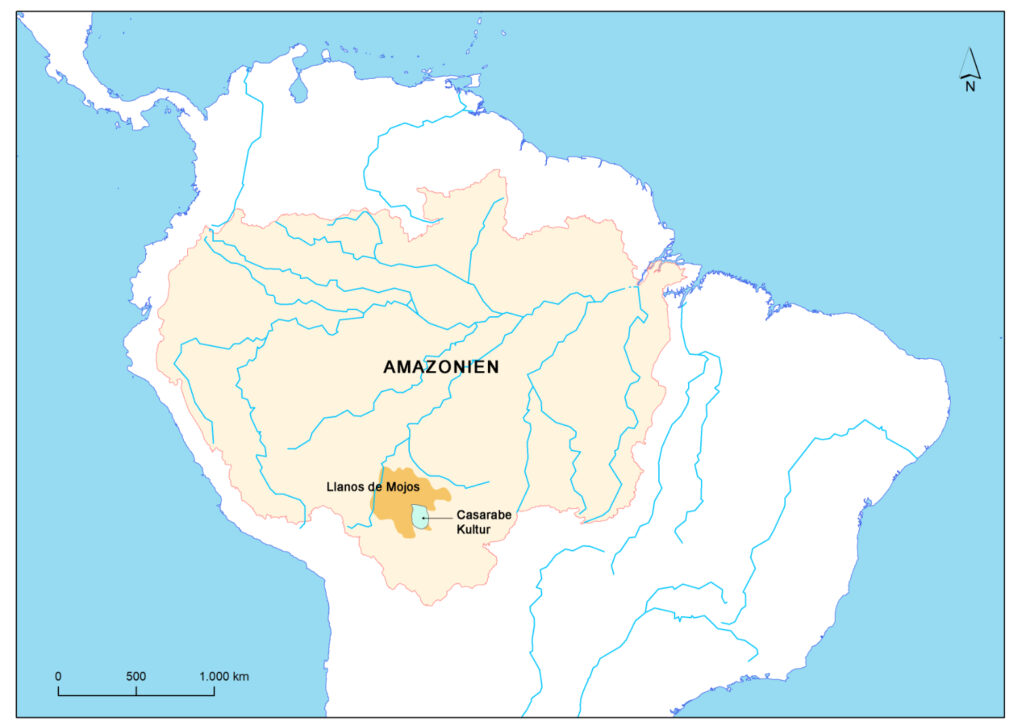

A team of international researchers, including Professor Jose Iriarte from the University of Exeter, has uncovered an array of intricate settlements in the Llanos de Mojos savannah-forest, Bolivia – that have laid hidden under the thick tree canopies for centuries.

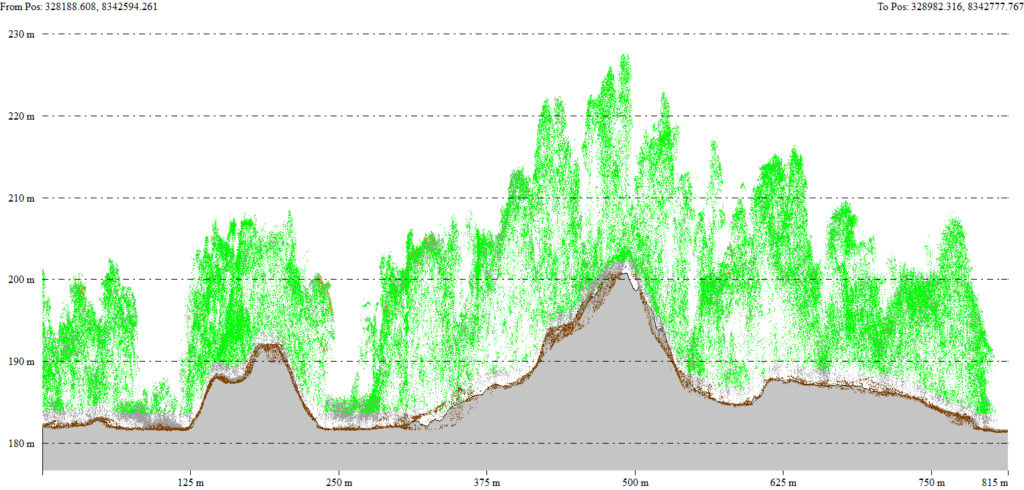

The cities, built by the Casarabe communities between 500-1400 AD, feature an unprecedented array of elaborate and intricate structures unlike any previously discovered in the region – including 5m high terraces covering 22 hectares – the equivalent of 30 football pitches – and 21m tall conical pyramids.

Researchers also found a vast network of reservoirs, causeways and checkpoints, spanning several kilometres.

The discovery, the researchers say, challenges the view of Amazonia as a historically “pristine” landscape, but was instead home to an early urbanism created and managed by indigenous populations for thousands of years.

Crucially, researchers maintain that these cities were constructed and managed not at odds with nature, but alongside it – employing successful sustainable subsistence strategies that promoted conservationism and maintained the rich biodiversity of the surrounding landscape.

The research, by Heiko Prümers, from the Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, Carla Jaimes Betancourt from the University of Bonn, José Iriarte and Mark Robinson from the University of Exeter, and Martin Schaich from the ArcTron 3D is published in the journal Nature.

Professor Iriarte said: “We long suspected that the most complex pre-Columbian societies in the whole basin developed in this part of the Bolivian Amazon, but evidence is concealed under the forest canopy and is hard to visit in person. Our lidar system has revealed built terraces, straight causeways, enclosures with checkpoints, and water reservoirs. There are monumental structures are just a mile apart connected by 600 miles of canals long raised causeways connecting sites, reservoirs and lakes.”

“Lidar technology combined with extensive archaeological research reveals that indigenous people not only managed forested landscapes but also created urban landscapes, which can significantly contribute to perspectives on the conservation of the Amazon.”

“This region was one of the earliest occupied by humans in Amazonia, where people started to domesticate crops of global importance such as manioc and rice. But little is known about daily life and the early cities built during this period.”

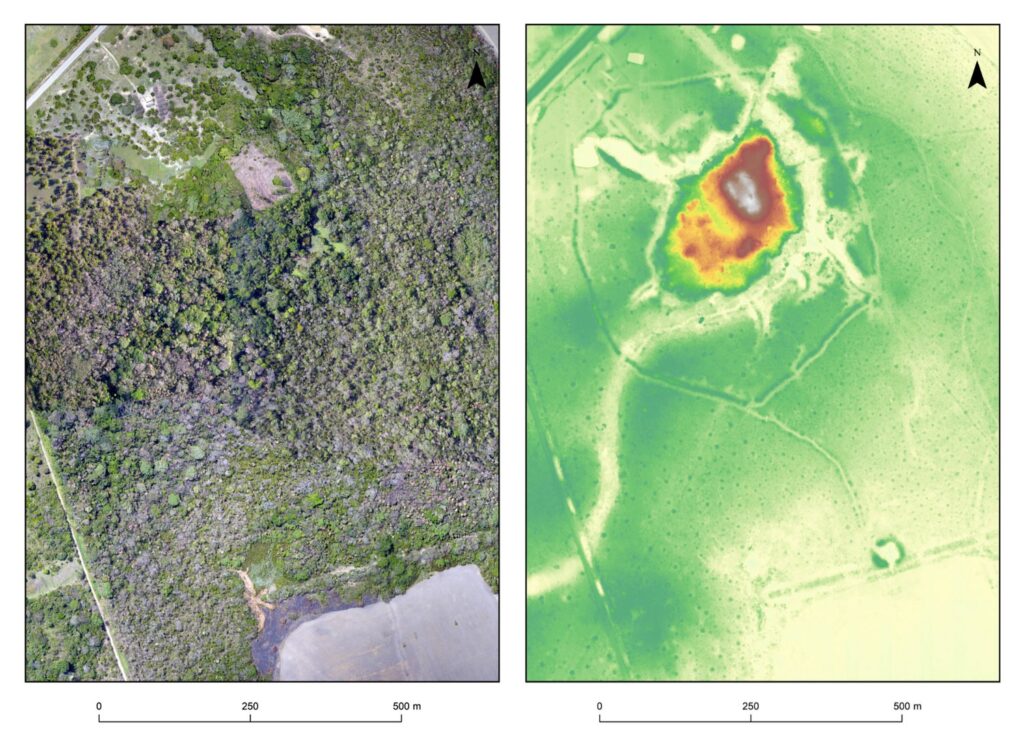

The team of experts used lidar technology – dubbed “lasers in the sky” – to peer through the tropical forest canopy and examine the sites, found in the savannah-forest of South West Amazonia.

The research revealed key insights into the sheer magnitude and magnificence of the civic-ceremonial centres found buried in the forest.

It showed that the core, central spread over several hectares, on top of which lay civic-ceremonial U-shaped structures, platform mounds and 21-m tall conical pyramids.

The research team conservatively suggest that the scale of labour and planning to construct the settlements has no precedents in Amazonia, and is instead comparable only with the Archaic states of the central Andes.

Crucially, the research team insist this new discovery gives a pivotal new insight into how this ancient urbanism was carried out sustainably and embracing conservationism.

At the same time the cities were built communities in the Llanos de Mojos transformed Amazonian seasonally flooded savannas, roughly the size of England, into productive agricultural and aquacultural landscapes.

The study shows that the indigenous people not only managed forested landscapes, but also created urban landscapes in tandem – providing evidence of successful, sustainable subsistence strategies but also a previously undiscovered cultural-ecological heritage.

Co-author, Dr Mark Robinson of the University of Exeter added: “These ancient cities were primary centres of a regional settlement network connected by still visible, straight causeways that radiate from these sites into the landscape for several kilometres. Access to the sites may have been restricted and controlled.

“Our results put to rest arguments that western Amazonia was sparsely populated in pre-Hispanic times. The architectural layout of Casarabe culture large settlement sites indicates that the inhabitants of this region created a new social and public landscape.

“The scale, monumentality and labour involved in the construction of the civic-ceremonial architecture, water management infrastructure, and spatial extent of settlement dispersal, compare favourably to Andean cultures and are to a scale far beyond the sophisticated, interconnected settlements of Southern Amazonia.”

Lidar reveals pre-Hispanic low-density urbanism in the Bolivian Amazon is published in Nature on Wednesday, May 25th 2022.

Press release from the University of Exeter.

Early urbanism found in the Amazon

Archaeologists reveal pre-Hispanic cities in Bolivia with laser technology LIDAR

Several hundred settlements from the time between 500 and 1400 AD lie in the Bolivian Llanos de Mojos savannah and have fascinated archaeologists for years. Researchers from the German Archaeological Institute, the University of Bonn and the University of Exeter have now visualized the dimensions of the largest known settlement of the so-called Casarabe culture. Mapping with the laser technology LIDAR indicates that it is an early urbanism with a low population density – the only known case so far from the Amazon lowlands. The results shed new light on how globally widespread and diverse early urban life was and how earlier societies lived in the Amazon. The study appeared in the journal Nature.

More than 20 years ago, Dr. Heiko Prümers from the German Archaeological Institute and Prof. Dr. Carla Jaimes Betancourt from the University of Bonn, at that time a student in La Paz, began archaeological excavations on two “mounds” near the village of Casarabe in Bolivia. The Mojos Plains is a southwestern fringe of the Amazon region. Even though the savannah plain, which flooded several months a year during rainy season, does not encourage permanent settlement, there are still many visible traces of the time before Spanish colonization at the beginning of the 16th century. Next to the “mounds”, these traces include mainly causeways and canals that often lead for kilometers in a dead straight line across the savannahs.

“This indicated a relatively dense settlement in pre-Hispanic times. Our goal was to conduct basic research and trace the settlements and life there,” says Heiko Prümers.

In earlier studies, the researchers already found that the Casarabe culture – named after the nearby village – dates to the period between 500 and 1400 AD and, according to current knowledge, extended over a region of around 16,000 square kilometers. The “mounds” turned out to be eroded pyramid stumps and platform buildings.

Initial conventional surveys revealed a terraced core area, a ditch-wall enclosing the site, and canals. In addition, it became apparent that some of these pre-Hispanic settlements were enormous in size.

“However, the dense vegetation under which these settlements were located prevented us from seeing the structural details of the monumental mounds and their surroundings,” says Carla Jaimes Betancourt from the Department for the Anthropology of the Americas at the University of Bonn.

LIDAR technology used in the Amazon for the first time

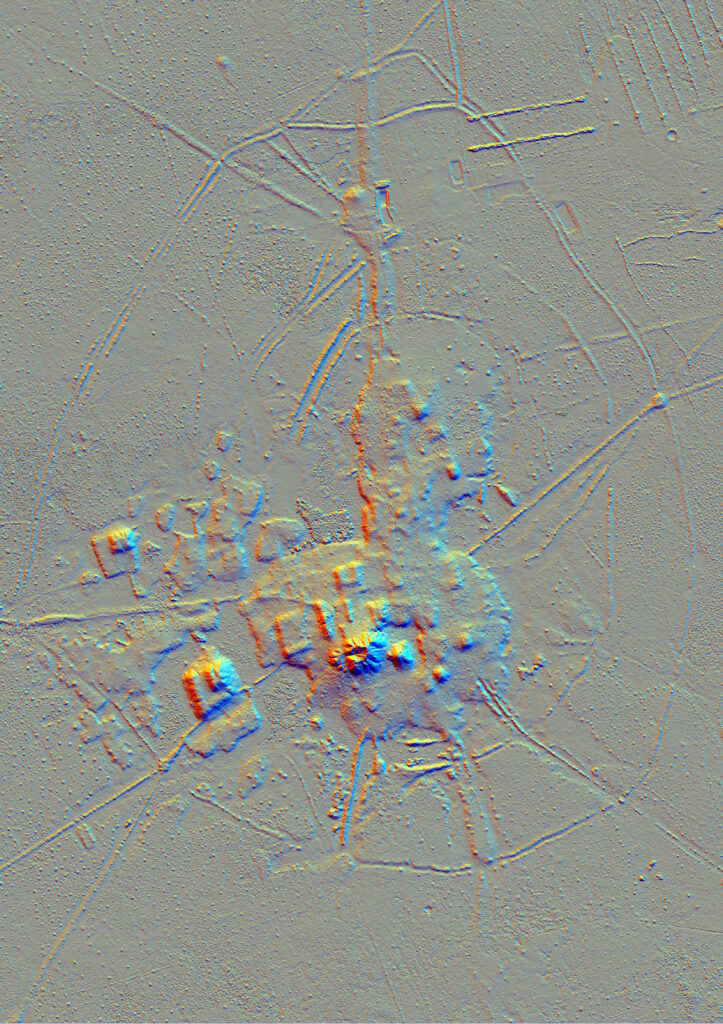

To find out more, the researchers used the airborne laser technology LIDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) for the first time in the Amazon region. This involves surveying the terrain with a laser scanner attached to a helicopter, small aircraft or drone that transmits around 1.5 million laser pulses per second. In a subsequent evaluation step, the vegetation is digitally removed creating a digital model of the earth’s surface, which can also be displayed as a 3D image.

“The first results were excellent and showed how effective the technology was even in dense rainforest. From that moment on, the desire arose to map the large settlements of the Casarabe culture using LIDAR technology,” says study leader Dr. Heiko Prümers.

For the current study, in 2019 the team together with Prof. Dr. José Iriarte and Mark Robinson from the University of Exeter, mapped a total of 200 square kilometers of the Casarabe cultural area. The evaluation done by the company ArcTron3 held a surprise. What came to light were two remarkably large sites of 147 hectares and 315 hectares in a dense four-tiered settlement system.

“With a north-south extension of 1.5 kilometers and an east-west extension of about one kilometer, the largest site found so far is as large as Bonn was in the 17th century,” says co-author Prof. Dr. Carla Jaimes Betancourt.

It is not yet possible to estimate how many people lived there.

“However, the layout of the settlement itself tells us that planners and many active hands were at work here,” says Heiko Prümers.

Modifications made to the settlement, for example the expansion of the rampart-ditch system, also speak to a reasonable increase in population.

“For the first time, we can refer to pre-Hispanic urbanism in the Amazon and show the map of the Cotoca site, the largest settlement of the Casarabe culture known to us so far,” Prümers emphasizes.

In other parts of the world similar agrarian cities with low population densities had already been found.

LIDAR shows anthropogenically altered landscape

LIDAR mapping reveals the architecture of the settlement’s large squares. Stepped platforms topped by U-shaped structures, rectangular platform mounds, and conical pyramids (up to 22 meters high). Causeway-like paths and canals connect the individual settlements and indicate a tight social fabric. At least one other settlement can be found within five kilometers of each of the settlements known today.

“So the entire region was densely settled, a pattern that overturns all previous ideas,” says Carla James Betancourt, who is a member of the Transdisciplinary Research Area “Present Pasts” at the University of Bonn.

The researchers emphasize that for all the euphoria about the site mappings and the possibilities they offer for reinterpreting the settlements in their geographic setting, the real archaeological work is just beginning. The goal for the future, they say, is to understand how these large regional centers functioned.

“Time is running out because the spread of mechanical agriculture is destroying a pre-Columbian structure every month in the Llanos de Mojos region, including mounds, canals, and causeways,” says Betancourt. With this in mind, Betancourt says, Lidar is not only a tool for documenting archaeological sites, but also for planning and preserving the impressive cultural heritage of the indigenous peoples of the Amazon.

Funding:

The study was funded by the German Archaeological Institute and the Ministry of Planning of the Plurinational State of Bolivia.

Publication: Heiko Prümers, Carla Jaimes Betancourt, José Iriarte, Mark Robinson & Martin Schaich: Lidar reveals pre-Hispanic low-density urbanism in the Bolivian Amazon. Nature; https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04780-4

Press release from the University of Bonn.