St. Francis Contemplating a Skull by Spanish painter Francisco de Zurbarán, for the first time in Rome

On loan from the Saint Louis Art Museum, the work will be exhibited

starting 16 March in the Hall of St. Petronilla at the Capitoline Museums,

alongside canvases by Caravaggio e Velázquez

St. Francis Contemplating a Skull, ca. 1635

oil on canvas, cm 91.4 x 30.5 Saint Louis, Saint Louis Art Museum, inv.47:1941

Rome, 16 March 2022 – For the first time, Rome will be placing the spotlight on the Spanish master Francisco de Zurbarán (1598-1664) who, alongside Diego Velázquez and Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, was one of the greatest representatives of Spanish painting during the so-called Siglo de Oro, the golden age of Spanish art.

Among the most impressive instances of the Spanish master’s mystical formalism, St. Francis Contemplating a Skull is on loan from the Saint Louis Art Museum, and its arrival at the Capitoline Museums, from 16 March to 15 May 2022, presents an exceptional opportunity to gain close-up understanding of his highly original pictorial language, the lessons of which were first understood by nineteenth-century French painters and recognized by Italian and international critics only beginning in the 1920s.

The Fortune Teller, 1597, oil on canvas, 115 x 150 cm Rome, Capitoline Museums, inv. PC 131

John the Baptist, 1602, oil on canvas, cm 129 x 94 Rome, Capitoline Museums, inv. PC 239

Moreover, the choice of staging the work in the museum’s St. Petronilla Hall places it in a dialogue with the two Caravaggio canvases present there – The Fortune Teller and John the Baptist – and with Diego Velázquez’s Portrait of Juan de Córdoba: four masterpieces, then, done over a fifty-year time frame, whose juxtaposition offers a reflection on the art of three key figures in seventeenth-century painting.

Portrait of Juan de Córdoba, ca. 1650, oil on canvas, 67 x 50 cm Rome, Capitoline Museums, inv. PC 62

Thee exhibition project Zurbarán a Roma. Il San Francesco del Saint Louis Art Museum tra Caravaggio e Velázquez (“Zurbarán in Rome. The Saint Louis Art Museum’s St. Francis between Caravaggio and Velázquez”) is promoted by Roma Culture, Sovrintendenza Capitolina ai Beni Culturali (the cultural heritage office of the city of Rome) and is curated by Federica Papi and Claudio Parisi Presicce. Organized by Zètema Progetto Cultura.

The Saint Louis Art Museum’s St. Francis Contemplating a Skull originally belonged to an altarpiece (retablo) conserved in the Carmelite church of the Monastery of San Alberto in Seville. In spite of its small size, it is one of the most fascinating depictions of the friar from Assisi.

The saint, a genuine pictorial obsession for the artist (who repeats the subject in other works over the course of his activity), is depicted standing, wearing his characteristic Capuchin frock while contemplating a skull he is holding in his hands. The composition’s severe and monumental appearance is accentuated by the strong geometric rigour, by the verticality of the hood, and by the folds in the garment that falls to the floor, leaving only the tips of the toes on his bare feet exposed. The silent dialogue between the saint and the skull symbolizes the passage from life to death, an allusion to the fragility of human existence, a recurring theme in Spanish Baroque art and in general the art of the Counter-Reformation.

The creative and visual process is therefore slow and not immediate as takes place in Caravaggio, and the lights and shadows do not take on a natural value, but a symbolic and spiritual one. In his ascetic contemplation of the skull, the saint proves detached and elusive, immersed in a mystical dimension that transcends the viewer’s perception.

The use of light is the focus of the juxtaposition between the Saint Louis Art Museum’s St. Francis and the Capitoline Picture Gallery’s Caravaggio and Velázquez paintings, highlighting the affinities but also the differences. In fact, although the relationship between form, space, time, and light is certainly their common denominator, the pictorial choices and the symbolic interpretation each artist gave of them differ a great deal.

The austere, severe, and rigorously geometric style with which Zurbarán builds his images; his ability to grasp, even in the simplest and humblest subjects, the poetic charm of existence; and his ability, through the contrast between his dark backgrounds and light foregrounds, to give his compositions monumentality and naturalism at the same time, saw him defined as a mystical, metaphysical, oneiric, and magical painter, and earned him the nickname “Spanish Caravaggio,” first ascribed to him by the Spanish biographer Antonio Palomino in his 1724 volume An account of the lives and works of the most eminent Spanish painters, sculptors and architects.

Although, of all Iberian painters, Zurbarán was the only one to earn this sobriquet, he never visited Italy. He became acquainted with Caravaggio’s revolutionary painting only via copies of the artist’s works that had already come to Spain in the first decade of the seventeenth century, and through observation of the works of Caravaggio’s followers, and Jusepe de Ribera above all. Moreover, Zurbarán’s works conserved in Italian territory are quite rare (only in Florence and Genoa), and only one show dedicated to the painter– organized in Ferrara in 2013 and without the Saint Louis painting – has been staged in Italy.

Starting from Caravaggio’s style, Zurbarán developed a wholly personal version of tenebrism, applying it to the figures of saints and to his extraordinary and hyperrealistic still lifes. For the Spanish painter, through light, “grace” is projected into the physical as well as into the spiritual world, as was affirmed in the mystical literature at that time, particularly in the Carmelite literature widespread in Catholic Spain.

INFO

Zurbarán a Roma. Il San Francesco del Saint Louis Art Museum tra Caravaggio e Velázquez. (“Zurbarán in Rome. The Saint Louis Art Museum’s St. Francis between Caravaggio and Velázquez”)

Capitoline Museums – Picture Gallery – St. Petronilla Hall

Piazza del Campidoglio, 1

Opens daily 9:30 AM – 7:30 PM (ticket office closes one hour earlier).

Tel.: 060608 (daily, 9:30 AM – 7:00 PM)

www.museicapitolini.org; www.museiincomune.it

———————————————————————————————————————————————————-

Francisco Zurbarán (1598-1664)

St. Francis Contemplating a Skull, ca. 1635

oil on canvas, cm 91.4 x 30.5 Saint Louis, Saint Louis Art Museum, inv.47:1941

This is one of the most intriguing portrayals of St. Francis of Assisi, Zurbarán’s pictorial obsession and namesake. Dressed in the cloak of the Friars Minor Capuchin, he is standing as he advances towards us while contemplating the skull he is holding in his hands. His head is bowed and his face is just glimpsed beneath the pointed hood that verticalizes the figure and is echoed in the shadow behind him. While the figure of the saint may at first glance resemble a model studied from life, it is in reality revealed to our eyes as an invention emerging slowly from the darkness and taking shape by effect of the divine light it is struck by. The nearly monochrome palette contributes to the rigour and the strong devotional austerity transmitted by the image of the saint absorbed in silent dialogue with the skull, reminding us of the fragility and brevity of human existence.

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1571-1610)

The Fortune Teller, 1597

oil on canvas, 115 x 150 cm Rome, Capitoline Museums, inv. PC 131

The painting is an important example of the explosive innovations that the artist introduced into painting. It depicts an episode of daily life that one might seemingly witness on any day when making one’s way through the piazzas and alleyways of late sixteenth-century Rome. Starting from the background of the canvas, Caravaggio builds an undefined space made real by the natural light that, as it invades the pictorial field, builds shapes and volumes. The subjects, a “gypsy” woman and a young knight, are live models in contemporary garb, depicted from live observation. However, the subject of the work is not only what is seen: the young and seductive “gypsy,” under the pretext of reading the knight’s future, takes him by the hand, and with a quick gesture slips the ring off his right ring finger – a clear warning not to be deceived, and not to give in to the seduction of false prophets.

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1571-1610)

John the Baptist, 1602

oil on canvas, cm 129 x 94 Rome, Capitoline Museums, inv. PC 239

The painting depicts a completely nude youth reclining on an animal skin and on white and red cloth, placing his arm around a ram and smiling as he turns towards the viewer. The light comes from the top left and strikes the youth’s nude back, part of his face, and his right leg, but leaving the rest of the body in shadow. In the work, Caravaggio makes the divine human and the human divine: Saint John is re-embodied as a grinning, impish and sensual youth, expressing with his whole body the joy of living. The boy in his turn interprets a young saint still unaware of his dramatic destiny. The figure appears to emerge suddenly from the darkness, and to take sudden shape before our eyes in a real space, under a real light, and in a real time – a figure it seems we can almost touch.

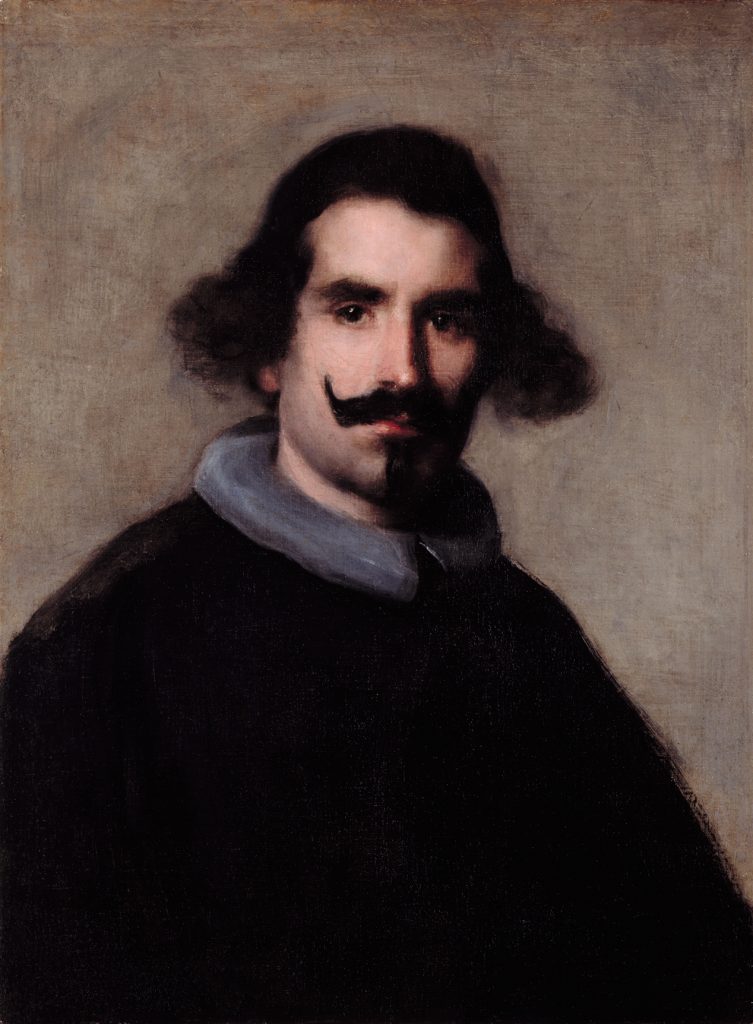

Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez (1599-1660)

Ritratto di Juan de Córdoba, ca. 1650

oil on canvas, 67 x 50 cm Rome, Capitoline Museums, inv. PC 62

The portrait depicts the agent of the Spanish Crown Juan de Córdoba, Velázquez’s right-hand man during his second Roman sojourn (1649-1651). The painting was in all likelihood made as an homage to his trusted friend, as the loose pictorial treatment and the practically sketched state of the garment also lead one to believe. Looking at the man’s face, we are left captivated by the subject’s gaze towards us. Velázquez in fact portrays not only the truth of his appearance, but his humanity, his most intimate thoughts, his individuality. This penetrating and at the same time romantic realism lays the person bare, and in it, form and appearance are not defined but only hinted at with a loose, quick brushstroke, in which the outlines appear to dissolve in the vibration of the man’s breathing.

Press release from the Zètema Progetto Cultura Press Office