Chemnitz historian Monja Schünemann brings to view previously unnoticed, invisible folding effects in Jean Fouquet’s “Melun Diptych”

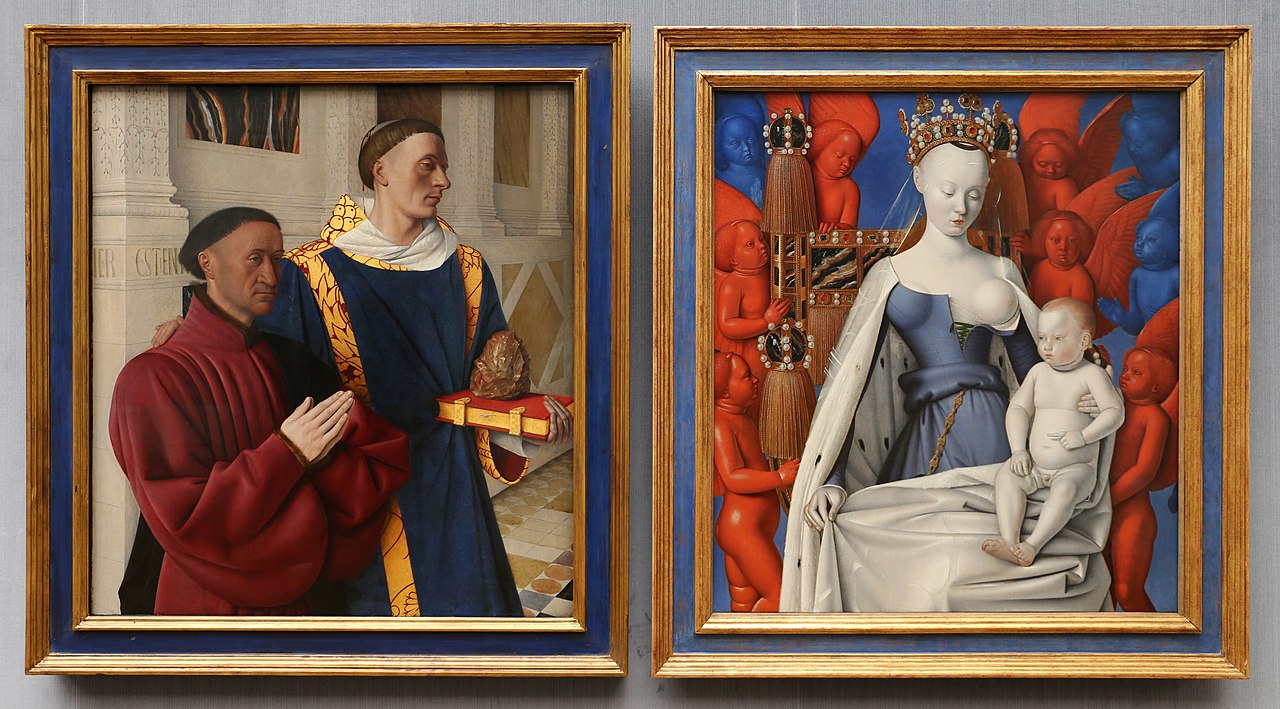

The “Melun Diptych” by the French book and panel painter Jean Fouquet is a famous work from the late Middle Ages. The two panels were created around 1455 and were first hung in a crypt of the Collegiate Church of Notre-Dame in Melun. Separated in the 18th century, today the right panel belongs to the Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp, the left panel to the Gemäldegalerie Berlin. The left panel shows the commissioner of the diptych, Étienne Chevalier – treasurer of the French kings Charles VII and Louis XI – kneeling next to his patron saint, St. Stephen. The right panel shows the Madonna breastfeeding the baby Jesus, surrounded by several angels. The complete diptych was shown in Paris in 1937 on the occasion of the World Exhibition and 80 years later in Berlin. Today the panels of the diptych can be seen again separately in both museums.

Despite this fact, Monja Schünemann, a research assistant at the Professorship of European History in the Middle Ages and Early Modern Period (head: Prof. Dr. Martin Clauss) at Chemnitz University of Technology, made a remarkable discovery during an excursion with history students from the university to the Gemäldegalerie Berlin:

“When I was intensively thinking about the composition of the entire diptych while looking at the left panel, a thought struck me like a bolt of lightning. On the same day, I made a mirror-image sketch of the panel on display in Berlin and superimposed it on the panel with the Madonna – I folded both panels together, so to speak. In the process, I discovered a previously unnoticed game of hide-and-seek that does not reveal itself when looking at the open double image. Only when one takes into account the folding effect of the panels, which are actually connected by a hinge, and which has only recently come increasingly into the focus of work in art history, do completely new interpretations of what Jean Fouquet probably also wanted to express open up”.

Schünemann describes her discovery.

“Closing the picture completely changed the image’s message, without viewers being able to physically see what was happening between the panels lying on top of each other“, Schünemann explains. In the resulting “sandwich image,” the donor Étienne Chevalier kneels in the folds of Mary’s wide-open cloak and is mystically nursed by her. “The two wings of the diptych thus become a lactatio, which in iconography denotes the miracle of nourishment from the Madonna’s breast. When the panels are folded together, it also becomes obvious that the Christ sitting on the Madonna’s lap can look into the chest of the breastfed and thus literally into the heart”.

“This can now also explain technological art studies of the past, which have shown that both Étienne Chevalier’s head and that of St. Stephen of Fouquet were corrected during painting,” says the Chemnitz historian. Accordingly, the painter wanted certain points of the picture to meet exactly when the diptych is closed and at that moment the donor Étienne Chevalier lies against Madonna’s breast and becomes the recipient of her nourishment. “The directions of the angels’ gazes on the right panel now also take on a previously unimagined meaning” says Schünemann.

Press release from Chemnitz University of Technology, by Matthias Fejes.