New findings on the Byzantine necropolis Tell es-Sin in Syria

A study published in the journal Bioarchaeology of the Near East reveals the features of the population that was buried in the necropolis of Tell es-Sin in Syria, a Byzantine archaeological site dating from the 5th to 7th centuries AC. located in the left side of the Euphrates River. The principal researchers of the new anthropological study on Tell es-Sin -in the middle of a transit area for the ancient Byzantine forces and the Persian Sassanids- are Laura Martínez, from the Faculty of Biology of the University of Barcelona, and Ferran Estebaranz-Sánchez, from the Faculty of Biosciences of the Autonomous University of Barcelona.

Other participants are the researcher Juan Luis Montero-Fenollós, lecturer from the University of la Coruña and director of the excavation project in the site of Tell es-Sin, and other experts from Maison de l’Orient et de la Méditerranée (France), the Yarmouk University (Jordan) and the Mykolas Romeris University (Lithuania).

Ancient Syria’s Hill of Teeth

The site of Tell es-Sin -from Arabic “Hill of Teeth”- covers an area of twenty-five hectares is divided into the acropolis, the lower town, and necropolis -which covers seven hecctares. It is in the south-eastern of the current city of Deir ez-Zor -frontier between Syria and Iraq- and it is considered a kastron, that is, a place with administrative and military functions. Both the size and urban structure of the site and its fortified nature suggest it would have been an ancient polis whose ancient name is still unknown.

Tell es-Sin represents one of the most important necropolis from the Fertile Crescent to the Near East, but authors say “it is still very much unknown”. The new study wants to focus on the knowledge of frontier populations in the Byzantine Empire during the 6th-7th centuries, a period in which necropolis and skeleton remains are not abundant.

A fortification in the middle of the military Near East

“Mesopotamia was a strategic defensive area regarding the entrances and invasions from the Persians and the Arabians. In this context, Tell es-Sin could have been affected by the territorial and military reorganization by the emperor Justinian, who promoted fortifications of lime populations in the middle of the 6th century”, notes Laura Martínez, lecturer at the Department of Evolutionary Biology, Ecology and Environmental Sciences at the Faculty of Biology, and first author of the study.

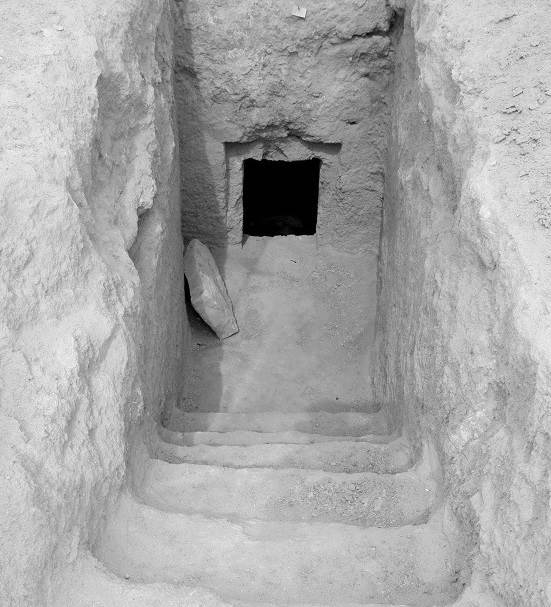

The first archaeological excavations of the Byzantine necropolis of Tell es-Sin date from 1978 and were led by Asad Mahmoud, general director of Antiquities and Museums in Deir ez-Zor at the moment. In 2005, the study of the first Syrian-Spanish archaeological mission -coordinated by the University of la Coruña- highlighted the relevance of the necropolis of Tell es-Sin, which was part of the Eastern limes Diocletianus together with Tell es-Kasra and Circesium (current Buseira). The experts identified a total of 170 hypogea in a necropolis that could have about one thousand tombs.

Tombs and Byzantine archaeology in Syrian territory

As Ferran Estebaranz-Sánchez notes, “samples from Tell es-Sin represent an heterogeneous and biased series of skeleton remains corresponding to tombs that were sacked during the years. This anthropological study wanted to provide information on the sex, age of death, height and other morphological variables of the excavated individuals in the site using traditional biometrics”.

The analysed sample -only a small part out of the total burials in Tell es-Sin -includes human remains from ten excavated hypogea in the Syrian-Spanish mission. A total of 71 individuals were analysed (at least, eighteen would correspond to men, and twelve to women).

According to the experts, they did not observe bias regarding sex or age in the studied remains, and they highlight the lack of children compared to other areas (they could have been buried in other niches in the entrance of the tomb). Likewise, there is at least between one and five individuals buried inside every niche (the average is three bodies per niche, including sub-adults and adults), according to the model of collective burial typical from ancient Syria.

Despite the fragmented state of the remains, the team could estimate the height of most individuals. “The average height we estimate considering the upper long bones is 174.5 for men and 159.1 for women. These figures are similar to those estimated with the diameter of the femur head: 176.1 cm for males and 164.5 for females”, notes Estebaranz Sánchez.

“In conclusion -he continues-, the estimated height for the Byzantine population in Tell es-Sin is similar to other contemporary Byzantine populations”.

About 25% of the individuals presented cribra orbitalia and 8.5% of porotic hyperostosis, alterations in brain bones associated to anaemia or lack of iron or vitamins, rickets, infection and other inflammatory conditions.

The prevalence of degenerative joint diseases was low, according to the study. Regarding dental samples, about 2.8% of teeth presented caries, lower figures compared to other contemporary byzantine sites in the area that could be related to a low sample analysed in Tell es-Sin.

Tell es-Sin: the end of a site with the arrival of Islam

The end of the site of Tell es-Sin -in the first quarter of the 7th century AC- coincided with the wars against the Persian Sassanids and Islamic Arabian tribes. Despite the conditions of the site of Tell es-Sin and the current situation -after the ISIS occupation- the discovery and excavation of graves that were not sacked is essential to study the knowledge of this population.

“This is why we are now analysing the buccal microstriations to infer the diet of the population and therefore complete the biocultural model of frontier populations with great ancient empires”, conclude Laura Martínez and Ferran Estebaranz Sánchez.

Article reference:

Martínez, L. M.; Estebaranz-Sánchez, F.; Khawam, R.; Anfruns, J.; Alrousan, M.; Pereira, P.; Pérez-Pérez, A.; Montero-Fenollós, J. L. “Human remains from Tell es-Sin, Syria, 2006-2007”. Bioarchaeology of the Near East, April, 2020.

Press release from the University of Barcelona