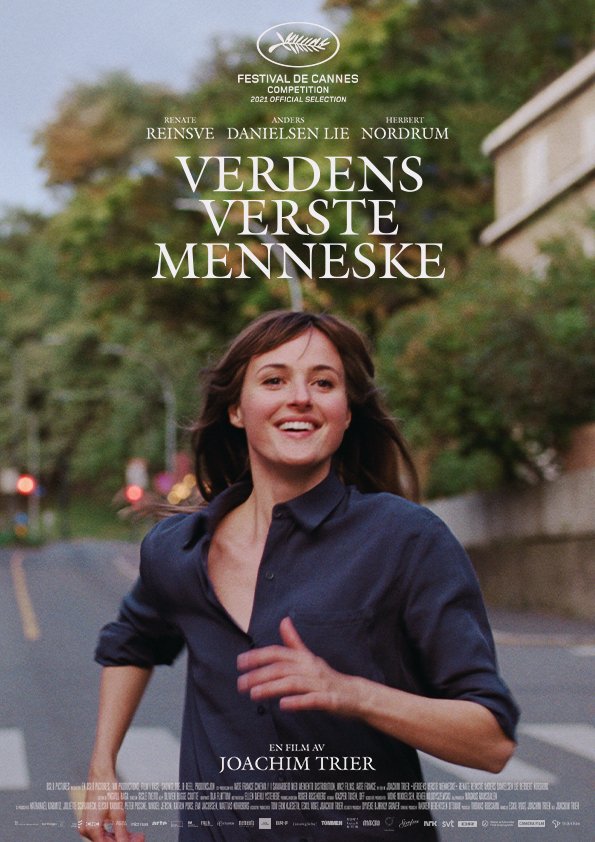

The best film of 2021: The Worst Person in the World

On my train back to London, after an intense working Wednesday in Oxford, less than a month ago, I was reading about the Oscar nominees for the Best International Feature Film. Apparently, everybody knows Drive My Car will win. And yet, another film, unquestionably the best film of 2021, is on the list, and to me it’s unbelievable it most likely won’t get the prize.

The Worst Person in the World is the antidote to the sloppy and sappy fake toxic positivity imposed on us millennials. Misguidedly labelled as “romantic comedy”, Joachim Trier’s third episode of his Oslo trilogy is everything but a comedy and only bitterly romantic. Its drama is divided into prologue, episodes, and epilogues, following a traditional – yet fragmented – narrative structure, and it develops through four years of the life of Julie (Renate Hansen), a very undecided (as to her job, her aspirations, and personal life plans) millennial woman.

She is torn between different ambitions, but most importantly between two intense love stories, Aksen (Anders Danielsen Lie), a very successful and provocative comic book writer, much older than her, whom she’s living with, and Eivind (Herbert Nordrum) a barista, closer to her in age, she casually meets at a wedding party she had crashed, and with whom an instant mental and physical connection develops.

Which of the three is “the worst person in the world”? This is a question the film doesn’t aim to answer. Because, I assume, none of them is. While one is led to blame and judge Julie for cheating, abandoning, and disappointing the ones she loves without too many regrets and second thoughts, in the end we cannot but empathise with her genuine struggles, her ever so pressuring doubts, her difficulties to fit into a lifestyle that other people (mostly Aksen and Eivind) are demanding from her. She’s fiercely fighting those doubts, making abrupt, rushed, and sometimes painful or hurtful choices – for her and for others. She’s the opposite of a generational stereotype. She isn’t in a hurry to be financially stable, to become a wife or a mother. She’s 30, her goals are still to be set – they’re still evolving; for Julie there is a lot more to explore, to love, and to experience. It is not time for her to stop and sum up, settled down, like many around her would expect.

The lightness with which Trier treats these struggles makes the story relatable to those who, like Julie, haven’t found the perfect recipe to gain success or peace. The cinematic expedients are simple but effective (e.g. time stopping and then restarting), the photography is highly evocative with a wonderful balance of dark and light tones, just like the personality of the protagonist.

The characters are complex and amazingly developed, each with their own battles to fight (Aksen against the controversial reception of his work, and then cancer; Eivind against those expecting him to do more in life than sell coffee); we get slowly used to their habits, their many contradictions. They’re dwelling in an embracing Oslo, a comforting yet confrontational city, a mirror of their personalities. The acting is superb – Renate Hansen, particularly, brings a rare depth to her character.

The Worst Person in the World is everything a person around 30 years old needs to see and remember: like Julie, we do try, we do fail, we don’t need to pretend all will go well. We don’t need to smile 24 hours a day; we will hurt people, we will hurt ourselves, we will regret our choices. We will make plans and unravel them. We will be told our time is running out. We will take a breath and accept that yes, time runs out, but also restarts, and it’s fine to take more of it if we need to. And while happiness is not a constant state, we can still feel deeply about things and people.

I watched this film on New Years’ Eve, drinking some Traminer my dad used to like. It really felt like an antidote to the poisonous images of lives incapsulated in stereotypes that I keep seeing around me. An antidote to the idea that everything must be fine in the end, if we compromise and end up accepting (too) soon less than we had demanded from our lives. It made me start the year well. Maybe only a bit sadly, but with a hint of hope, hope that things are never over. That there’s a new you each time you want. That we can change our minds any time we find it necessary or useful. That love doesn’t end but evolves. That pain can be overcome. That happy endings are overrated. That all endings are.

So, a part of me still hopes this film might win an Academy Award this year. No offence to our dear Paolo Sorrentino, his beloved Maradona, and acclaimed Japanese blockbusters.