Findings from 3,000-year-old Uluburun shipwreck reveal complex trade network

Findings offer glimpse into life 3,000-plus years ago

More than 3,000 years before the Titanic sunk in the North Atlantic Ocean, another famous ship wrecked in the Mediterranean Sea off the eastern shores of Uluburun — in present-day Turkey — carrying tons of rare metal. Since its discovery in 1982, scientists have been studying the contents of the Uluburun shipwreck to gain a better understanding of the people and political organizations that dominated the time period known as the Late Bronze Age.

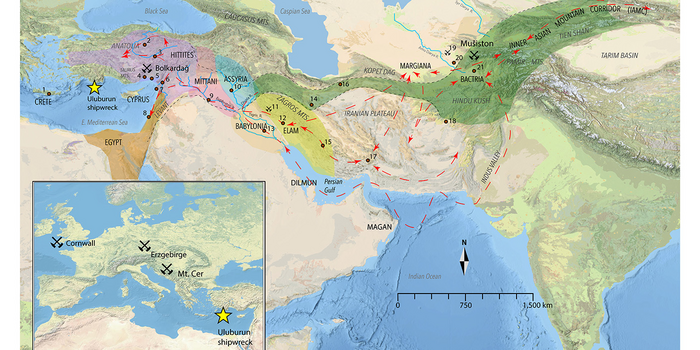

Now, a team of scientists, including Michael Frachetti, professor of archaeology in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis, have uncovered a surprising finding: small communities of highland pastoralists living in present-day Uzbekistan in Central Asia produced and supplied roughly one-third of the tin found aboard the ship — tin that was en route to markets around the Mediterranean to be made into coveted bronze metal.

The research, published on November 30 in Science Advances, was made possible by advances in geochemical analyses that enabled researchers to determine with high-level certainty that some of the tin originated from a prehistoric mine in Uzbekistan, more than 2,000 miles from Haifa, where the ill-fated ship loaded its cargo.

But how could that be? During this period, the mining regions of Central Asia were occupied by small communities of highlander pastoralists — far from a major industrial center or empire. And the terrain between the two locations — which passes through Iran and Mesopotamia — was rugged, which would have made it extremely difficult to pass tons of heavy metal.

Frachetti and other archaeologists and historians were enlisted to help put the puzzle pieces together. Their findings unveiled a shockingly complex supply chain that involved multiple steps to get the tin from the small mining community to the Mediterranean marketplace.

“It appears these local miners had access to vast international networks and — through overland trade and other forms of connectivity — were able to pass this all-important commodity all the way to the Mediterranean,” Frachetti said.

“It’s quite amazing to learn that a culturally diverse, multiregional and multivector system of trade underpinned Eurasian tin exchange during the Late Bronze Age.”

Adding to the mystique is the fact that the mining industry appears to have been run by small-scale local communities or free laborers who negotiated this marketplace outside of the control of kings, emperors or other political organizations, Frachetti said.

“To put it into perspective, this would be the trade equivalent of the entire United States sourcing its energy needs from small backyard oil rigs in central Kansas,” he said.

About the research

The idea of using tin isotopes to determine where metal in archaeological artifacts originates dates to the mid-1990s, according to Wayne Powell, professor of earth and environmental sciences at Brooklyn College and a lead author on the study. However, the technologies and methods for analysis were not precise enough to provide clear answers. Only in the last few years have scientists begun using tin isotopes to directly correlate mining sites to assemblages of metal artifacts, he said.

“Over the past couple of decades, scientists have collected information about the isotopic composition of tin ore deposits around the world, their ranges and overlaps, and the natural mechanisms by which isotopic compositions were imparted to cassiterite when it formed,” Powell said. “We remain in the early stages of such study. I expect that in future years, this ore deposit database will become quite robust, like that of Pb isotopes today, and the method will be used routinely.”

Aslihan K. Yener, a research affiliate at the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World at New York University and a professor emerita of archaeology at the University of Chicago, was one of the early researchers who conducted lead isotope analyses. In the 1990s, Yener was part of a research team that conducted the first lead isotope analysis of the Uluburun tin. That analysis suggested that the Uluburun tin may have come from two sources — the Kestel Mine in Turkey’s Taurus Mountains and some unspecified location in central Asia.

“But this was shrugged off since the analysis was measuring trace lead and not targeting the origin of the tin,” said Yener, who is a co-author of the present study.

Yener also was the first to discover tin in Turkey in the 1980s. At the time, she said the entire scholarly community was surprised that it existed there, right under their noses, where the earliest tin bronzes occurred.

Some 30 years later, researchers finally have a more definitive answer thanks to the advanced tin isotope analysis techniques: One-third of the tin aboard the Uluburun shipwreck was sourced from the Mušiston mine in Uzbekistan. The remaining two-thirds of the tin derived from the Kestel mine in ancient Anatolia, which is in present-day Turkey.

Findings offer glimpse into life 2,000-plus years ago

By 1500 B.C., bronze was the “high technology” of Eurasia, used for everything from weaponry to luxury items, tools and utensils. Bronze is primarily made from copper and tin. While copper is fairly common and can be found throughout Eurasia, tin is much rarer and only found in specific kinds of geological deposits, Frachetti said.

“Finding tin was a big problem for prehistoric states. And thus, the big question was how these major Bronze Age empires were fueling their vast demand for bronze given the lengths and pains to acquire tin as such a rare commodity. Researchers have tried to explain this for decades,” Frachetti said.

The Uluburun ship yielded the world’s largest Bronze Age collection of raw metals ever found — enough copper and tin to produce 11 metric tons of bronze of the highest quality. Had it not been lost to sea, that metal would have been enough to outfit a force of almost 5,000 Bronze Age soldiers with swords, “not to mention a lot of wine jugs,” Frachetti said.

“The current findings illustrate a sophisticated international trade operation that included regional operatives and socially diverse participants who produced and traded essential hard-earth commodities throughout the late Bronze Age political economy from Central Asia to the Mediterranean,” Frachetti said.

Unlike the mines in Uzbekistan, which were set within a network of small-scale villages and mobile pastoralists, the mines in ancient Anatolia during the Late Bronze Age were under the control of the Hittites, an imperial global power of great threat to Ramses the Great of Egypt, Yener explained.

The findings also show that life 2,000-plus years ago was not that different from what it is today.

“With the disruptions due to COVID-19 and the war in Ukraine, we have become aware of how we are reliant on complex supply chains to maintain our economy, military and standard of living,” Powell said. “This is true in prehistory as well. Kingdoms rose and fell, climatic conditions shifted and new peoples migrated across Eurasia, potentially disrupting or redistributing access to tin, which was essential for both weapons and agricultural tools.

“Using tin isotopes, we can look across each of these archaeologically evident disruptions in society and see connections were severed, maintained or redefined. We already have DNA analysis to show relational connections. Pottery, funerary practices, etc., illustrate the transmission and connectivity of ideas. Now with tin isotopes, we can document the connectivity of long-distance trade networks and their sustainability.”

More clues to explore

The current research findings settle decades-old debates about the origins of the metal on the Uluburun shipwreck and Eurasian tin exchange during the Late Bronze Age. But there are still more clues to explore.

After they were mined, the metals were processed for shipping and ultimately melted into standardized shapes — known as ingots — for transporting. The distinct shapes of the ingots served as calling cards for traders to know from where they originated, Frachetti said.

Many of the ingots aboard the Uluburun ship were in the “oxhide” shape, which was previously believed to have originated in Cyprus. However, the current findings suggest the oxhide shape could have originated farther east. Frachetti said he and other researchers plan to continue studying the unique shapes of the ingots and how they were used in trade.

In addition to Frachetti, Powell and Yener, the following researchers contributed to the present study: Cemal Pulakat at Texas A&M University, H. Arthur Bankoff at Brooklyn College, Gojko Barjamovic at Harvard University, Michael Johnson at Stell Environmental Enterprises, Ryan Mathur at Juniata College, Vincent C. Pigott at the University of Pennsylvania Museum and Michael Price at the Santa Fe Institute.

The study was funded in part by a Professional Staff Congress-City University of New York Research Award, in addition to a research grant from the Institute for Aegean Prehistory.

Press release from Washington University in St. Louis on the complex trade network revealed by Uluburun shipwreck.

Empires and entrepreneurs

Metal ingots from ancient shipwreck reveal path of prehistoric globalization

HUNTINGDON, Pa.—The captain tracked turbid clouds gathering above the roiling seas. Timbers groaned, and sailors shouted, scrambling across the heaving deck in a futile effort to reach the safety of a cove along the Uluburun peninsula.

The shipwreck dating to the 14th century B.C. was rediscovered off the coast of modern-day Turkey in 1982, along with a wealth of information for a research team of geologists, anthropologists, archaeologists, linguists, geographers, and historians.

“When I first saw pictures of the ship, I saw it as an amazing opportunity to use my isotope science to trace metal sources,” said Juniata College professor of geology Ryan Mathur, a member of the team that co-authored, “Tin from Uluburun shipwreck shows small-scale commodity exchange fueled continental tin supply across Late Bronze Age Eurasia,” published in the most recent issue of Science Advances.

The ship was laden in luxury cargo, likely bound for a Mycenaean palace in mainland Greece.

“There were extraordinary things found on the shipwreck, which was porting raw materials, gifts, swords, daggers, metal ingots, and all sorts of semi-precious stones,” said K. Aslihan Yener of Institute for the Study of the Ancient World at New York University (ISAW). “It’s a fabulous discovery.”

Mathur learned of the project from Wayne Powell of Brooklyn College—CUNY, the two of whom had collaborated on tin and bronze studies for a decade.

“I think this has been the most exciting study of my career. The Uluburun shipwreck is iconic,” said Powell. “It’s described in every study or analysis of ancient trade in the Mediterranean and is foundational to our understanding of large-scale commodity trading between the major Bronze Age kingdoms, including Egypt, Mycenae, and the Hittites of Anatolia.”

Powell had been particularly interested in Mathur’s prior work in determining the origin of copper ore through isotopic analysis and if it would translate to tin.

“I had published research on the subject, and getting material like this to test was a really big deal,” Mathur said. “It was an opportunity to use a new technique to measure tin isotopes from a famous site.”

The researchers set out to understand more about the origins of the Uluburun shipwreck’s copper and tin ingots used in manufacturing bronze, a substance upon which empires were built or destroyed.

“We have very belligerent empires and kingdoms, with very complicated trade networks providing essential raw materials for their economies and their ambitions, warring with each other,” Yener said. “Their most vital defense mechanism is bronze weaponry. Tin was essential to making good bronze.”

Evidence of copper mining sites appeared throughout the historical and archaeological records. The origin of the tin was a mystery.

“No one could prove where any of the tin mining was happening. There were ideas there were mines in Turkey; Cornwall, England; Germany; and Tajikistan,” said Mathur. “Cornwall’s mining was huge and, being in the west, a lot of people thought it was the primary source of tin throughout the Bronze Age.”

An alternative hypothesis suggested the tin may have come from the east rather than the west.

“Everyone thought tin came from some exotic place in Central Asia, but the source was never specified,” Yener said. “Tablets that talked about these sources of tin date to a thousand years after tin started to be used in the Middle East,”

The ingots were excavated from the shipwreck site by Cemal Pulak of Texas A&M University, who had maintained the samples for decades. Mathur and Powell requested samples for analysis, and Pulak was glad to oblige.

“Isotopes provide a fingerprint to identify where people mined the metal,” said Mathur. “We’ve studied approximately 1,500 samples (1,000 bronze/tin artifacts and 425 tin ores) from all over the earth, so we can define ranges where the tin might have been mined. We were able to look at samples from all over the place, compare them, and come to a conclusion. It’s like a miracle.”

Two-thirds of the tin ingots came from Turkey, not far from the shipwreck site, despite archaeological evidence that one of the sources of tin, Kestel tin mine, had ceased production hundreds of years earlier. But there were other tin deposits in the Taurus Mountains with evidence of later working. The remainder of the tin was traced to Central Asia, signaling robust trade routes linking Asia and Europe predating the fabled Silk Road by centuries.

“That meant mining switched from an organized, industrial model to small-scale, decentralized mining of stream tin, and this then fed into a central point for processing,” Powell said, describing the method used to retrieve the ore as akin to panning for gold.

Ordinary citizens in areas once considered Bronze Age backwaters, not empires, independently met the demand and dictated the manner of trade.

“As this paper evolved, it reframed the story of what these suppliers of rare resources to major empires of the Mediterranean were like,” said Michael Frachetti of Washington University in St. Louis, Mo.

Each member of the team, Mathur, Frachetti, Powell, Yener, Pulak, H. Arthur Bankoff of Brooklyn College—CUNY, Gojko Barjamovic of Harvard University, Michael Johnson of Stell Environmental Enterprises, Vincent C. Pigott of the University of Pennsylvania Museum, and Michael Price of Santa Fe Institute, contributed a piece of the puzzle to complete an image of prehistoric globalization.

“These were nomads, herders, and communities with different adaptations. They were able to shape the market. These origin sites do not have urban populations and were not dictated by imperial politics,” Frachetti said. “The idea that tin was making its way to the Mediterranean, then smelted into bars, is amazing. Goods were flowing worldwide thousands of years before the modern era.”

Bibliographic information:

Tin from Uluburun shipwreck shows small-scale commodity exchange fueled continental tin supply across Late Bronze Age Eurasia, Science Advances (30-Nov-2022), DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.abq3766

Press release from Juniata College on the complex trade network revealed by Uluburun shipwreck.