A new study reveals the earliest evidence of opium use in the Land of Israel

A joint study by the Israel Antiquities Authority, Tel Aviv University and the Weizmann Institute of Science

A joint study by the Israel Antiquities Authority, Tel Aviv University and the Weizmann Institute of Science reveals the world’s earliest evidence of opium use

- Opium residue was found in pottery vessels excavated at Tel Yehud, dating back to the 14th century BC.

- According to the researchers, the Canaanites used the psychoactive drug as an offering for the dead.

A new study by the Israel Antiquities Authority, Tel Aviv University and The Weizmann Institute of Science has revealed the earliest known evidence of the use of the hallucinogenic drug opium, and psychoactive drugs in general, in the world. The opium residue was found in ceramic vessels discovered at Tel Yehud, in an excavation conducted by Eriola Jakoel on behalf of the Antiquities Authority. The vessels that contained the opium date back to the 14th century BC, and they were found in Canaanite graves, apparently having been used in local burial rituals. This exciting discovery confirms historical writings and archeological hypotheses according to which opium and its trade played a central role in the cultures of the Near East.

The research was conducted as part of Vanessa Linares’s doctoral thesis, under the guidance of Prof. Oded Lipschits and Prof. Yuval Gadot of Tel Aviv University’s Department of Archeology and Prof. Ronny Neumann of the Weizmann Institute, in collaboration with Eriola Jakoel and Dr. Ron Be’eri of the Israel Antiquities Authority, and The study was published in the journal Archaeometry.

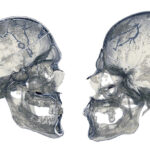

In 2012, the Antiquities Authority conducted a salvage excavation at the Tel Yehud site, prior to the construction of residences there. A number of Canaanite graves from the Late Bronze Age were found in the excavation, and next to them burial offerings – vessels intended to accompany the dead into the afterlife. Among the pottery, a large group of vessels made in Cyprus and referred to in the study as “Base-Ring juglets,” stood out.

Because the vessels are similar in shape to the poppy flower when it is closed and upside down, the hypothesis arose already in the 19th century that they were used as ritual vessels for the drug. Now, an organic residue analysis has revealed opium residue in eight vessels, some local and some made in Cyprus. This is the first time that opium has been found in pottery in general, and in Base-Ring vessels in particular. It is also the earliest known evidence of the use of hallucinogens in the world.

Dr. Ron Be’eri of the Israel Antiquities Authority says, “In the excavations conducted at Tel Yehud to date, hundreds of Canaanite graves from the 18th to the 13th centuries BC have been unearthed. Most of the bodies buried were those of adults, of both sexes. The pottery vessels had been placed within the graves were used for ceremonial meals, rites and rituals performed by the living for their deceased family members. The dead were honored with foods and drinks that were either placed in the vessels, or consumed during a feast that took place over the grave, at which the deceased was considered a participant. It may be that during these ceremonies, conducted by family members or by a priest on their behalf, participants attempted to raise the spirits of their dead relatives in order to express a request, and would enter an ecstatic state by using opium. Alternatively, it is possible that the opium, which was placed next to the body, was intended to help the person’s spirit rise from the grave in preparation for the meeting with their relatives in the next life”.

Vanessa Linares of Tel Aviv University explains: “This is the only psychoactive drug that has been found in the Levant in the Late Bronze Age. In 2020, researchers discovered cannabis residue on an altar in Tel Arad, but this dated back the Iron Age, hundreds of years after the opium in Tel Yehud. Because the opium was found at a burial site, it offers us a rare glimpse into the burial customs of the ancient world. Of course, we do not know what the opium’s role was in the ceremony – whether the Canaanites in Yehud believed that the dead would need opium in the afterlife, or whether it was the priests who consumed the drug for the purposes of the ceremony. Moreover, the discovery sheds light on the opium trade in general. One must remember that opium is produced from poppies, which grew in Asia Minor – that is, in the territory of current-day Turkey – whereas the pottery in which we identified the opium were made in Cyprus. In other words, the opium was brought to Yehud from Turkey, through Cyprus; this of course indicates the importance that was attributed to the drug.”

Dr. Ron Be’eri of the Antiquities Authority adds, “Until now, no written sources have been discovered that describe the exact use of narcotics in burial ceremonies, so we can only speculate what was done with opium. From documents that were discovered in the Ancient Near East, it appears that the Canaanites attached great importance to ‘satisfying the needs of the dead’ through ritual ceremonies performed for them by the living, and believed that in return, the spirits would ensure the health and safety of their living relatives.”

According to Eli Eskosido, director of the Israel Antiquities Authority, “New scientific capabilities have opened a window for us to fascinating information and have provided us with answers to questions that we never would have dreamed of finding in the past. One can only imagine what other information we will be able to extract from the underground discoveries that will emerge in the future.”

Bibliographic information:

Vanessa Linares, Eriola Jakoel, Ron Be’eri, Oded Lipschits, Ronny Neumann, Yuval Gadot, Opium trade and use during the Late Bronze Age: Organic residue analysis of ceramic vessels from the burials of Tel Yehud, Israel, Archaeometry (2-Jul-2022), DOI: 10.1111/arcm.12806, link: http://doi.org/10.1111/arcm.12806

Press release from the Israel Antiquities Authority, Tel Aviv University and the Weizmann Institute of Science